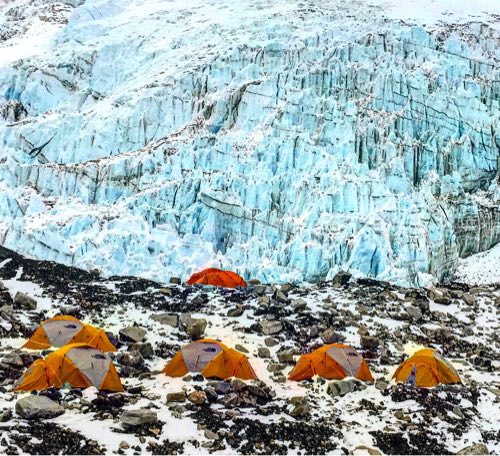

I am writing this from the Everest’s Camp 2 perched at an altitude of 6500m. In the past week I met at least three members of a filming crew collaborating with Endemol, a Dutch company that has given us the joy of The Big Brother TV reality show. Their job here on Everest is to shoot enough footage to create a virtual reality experience of climbing the world’s tallest mountain.

I have rather mixed feelings about this project. On the one hand, we know that Everest attracts climbers of mixed ability levels and that the public has been made aware of the environmental impact of climbing. In fact, when I pose a question ‘Should the Nepalese government limit the permit numbers here?’ to Ang Dorji, a 17 times summiteer of Everest. His answer is a resolute ‘Yes!’ ‘Due to skill shortage or an environmental impact?’. ‘Hands down, skills shortage of climbers’. Ang Dorji is a giant of a man who saved multiple lives and some may remember from the movie ‘Everest’ . He has a strong handle on the safety issue at hand. He knows both what it takes to summit and to secure the pathway. it was him who jointly with Anatoli Boukreev have pioneered rope fixing of the summit ridge in early 1990s by dragging hundreds of meters of rope tied to their waist.

Another argument for limiting numbers, of course, is the impact on the environment. I was intrigued that Ang Dorji downplayed this as a reason to restrict the number of issued permits. In his view, the mountain has changed though he reckons it’s mostly due to the effect of the climate change. He believes Everest is a much cleaner mountain since the year 2000 when climbing groups started to be taxed and were ordered to take down waste and empty oxygen bottles. In other words, an economic approach to the issue helped limit the damage.

Back to the VR experience – yes, it may help limit the leisurely interest of poorly prepared climbers who come here to take on a formidable and at times deadly challenge. But somehow I fear that by encouraging a range of VR experiences, Everest aside, we would limit the spread of the therapeutic impact that mountaineering and walking has on one’s physical and mental health.

In the past few days, there has been a public discussion in the UK papers with mountaineering grandees like Sir Chris Bonnington weighing in on the need to restrict the numbers of hill-walkers on public pathways to protect the land for future generations. This exchange of views coincided with the crowdfunding call by the British Mountaineering Council to raise £100,000 to help repair walkways. You can’t fault BMC for stirring this controversy. After all, effective fundraising drives are bound to exaggerate the issue in order to attract maximum attention.

All of that said, prohibition is a poor public policy choice and has rarely yielded results. More than anything , it surely produces a conflicting message to the public if the government is endorsing the need for a more active lifestyle but then issuing a call to protect pathways by encouraging restricted access. To say nothing about the scale of numbers that simply do not stack up: BMC’s call to raise £100,000 pales in comparison with the ballooning deficit in public healthcare funding due to an increase in the rates of obesity.

Having benefited enormously from being active in the elements, my strong view would be to further encourage rambling, hill walking and mountaineering. Perhaps, a modest tax – an access fee designed specifically for repair of the hill-walking pathways – is an answer. It is time we use Big Lottery’s money for the conservation and not the policy of restricting public access. Otherwise, all our kids will know would be a virtual reality show, formerly known as ‘great outdoors’.

Leave a Reply